ADVOCACY TRAINING PACKAGE: An Updated Version of the Action Letter Portfolio

A Step-by-Step Guide to Advocating for Change for People with Disabilities

Updated by E Zhang

Original by Glen W. White, Richard Thomson, and Dorothy E. Nary

Acknowledgements

This Advocacy Training Package is an updated version of the Action Letter Portfolio developed by Glen W. White, Richard Thomson, and Dorothy E. Nary in 1998. In the 20 years since, the internet has changed our options for communicating, so this new version includes chapters on using email and social media to advocate for your disability-related concerns.

This update would not have been possible without the previous work by the authors and the expertise and assistance of a number of organizations and individuals.

Thanks to center for independent living (CIL) directors Ann Branden, Mary Holloway, and Mike Oxford for their cooperation and support in helping with the development and evaluation of the original Action Letter Portfolio.

Thanks to consumers from Independence, Inc. for their participation and feedback in the testing of this revised manual.

Special thanks to the following individuals who drew on their vast experience in independent living and advocacy to provide valuable manual input to both the Action Letter Portfolio and the current manual.

- Bob Mikesic (both versions)

- Mary Olson

- Stephanie Sanford

- Rosie Cooper

- Mike Oxford

- Barb Knowlen

I wish you success in your advocacy efforts!

© 2018

-E (Alice) Zhang

Produced by:

Research and Training Center on Independent Living The University of Kansas

1000 Sunnyside Avenue, Room 4089

Lawrence, KS 66045-7555

Phone: 785-864-4095

Email: rtcil@ku.edu Website: rtcil.org

The contents of this training manual were developed under a grant from the Dole Institute of Politics’ 2015 “commemorateADA” initiative through a gift from the General Electric Company. The contents of this training manual do not necessarily represent the policy of the Robert J. Dole Institute of Politics, and you should not assume endorsement by the same.

Table of Contents

Introduction: Be a Disability Rights Advocate

Chapter 1: Task Analysis of a Disability-Related Advocacy Concern

Chapter 2: How to Write an Advocacy Letter

Chapter 3: Practice Writing an Advocacy Letter

Chapter 5: Writing an Advocacy Email

Chapter 6: Making an Advocacy Phone Call

Chapter 7: Advocacy through Social Media

Chapter 10: Resources on Disability and Advocacy

Introduction:Be a Disability Rights Advocate

By E Zhang

1. Why do we need to advocate?

Being an advocate simply means that you know what change you want and how to speak up for it. For example, as a wheelchair user you can advocate for raising your work desk so you can get your legs under. Or, as a student, you can advocate for extra time to take a test or a private testing room because of needs related to your ADHD. Advocacy can range from fighting for your own interests and rights to doing systemic advocacy, where you are fighting for your and others’ rights (e.g., accessible public transit buses). Being a self-advocate is important for a person’s wellbeing and success. The skill of advocacy crosses sociodemographic characteristics of age, gender, race, ethnicity, education, and disability.

Being an effective advocate is especially important for people with disabilities, since we often face a variety of disability-related concerns to achieve greater personal dignity, choice, and independence. The passage of legislation such as the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990, the Fair Housing Amendments Act of 1988 (FHAA) and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) of 1990 have granted people with disabilities new rights and protections. However, many attitudinal, economic, social and physical/environmental barriers continue to threaten their full participation to society.

For example, as a student with a disability, you may have experienced lower expectations from teachers. As a worker with a disability, you may have experienced struggles of obtaining and/or maintaining a job because of an employer’s unwillingness to provide reasonable accommodations. As a renter with a disability, you may have had difficulties with finding a home to accommodate your service animal. As a traveler with a disability, you may have stayed in many “so-called” ADA accessible hotel rooms that do not comply with ADA accessibility guidelines. As a consumer with a disability, you may have gone to restaurants where the restroom stall doors did not fully close, or where the toilets were too low, or too high, or the signs were not in braille. Most people with disabilities, whether physical or mental, visible or invisible, encounter prejudice or discrimination that makes life harder.

Given the barriers and challenges that individuals with disabilities face, we need to be vigilant to defend our own interests, and fight discrimination and inequality. We should and can learn to advocate for our personal and professional goals, and for others.

Laws are not effective unless they are enforced. In order for the ADA and other such laws to protect our civil rights, we must advocate for their use and enforcement. We need to learn how to bring our concerns to the attention of those who can affect change. While advocacy groups at the local, state, and national levels can address many of these concerns, individuals with disabilities can also make their voices heard to effect significant changes in their own neighborhoods and communities. In order to bring about change more quickly and efficiently, it benefits us to improve our personal advocacy skills.

2. How do we advocate?

To be an advocate, you have to think and act like an advocate. It may be true that some people are natural advocates, while others benefit from learning from more experienced people how to advocate. In order to learn more about advocacy, we conducted a focus group with well- seasoned disability advocates and sent out a national survey to disability rights advocates. We found that disability rights advocates used a variety of methods to advocate at both individual and systems levels. No one approach works for every kind of issue. Advocating with an office manager might take a different approach than meeting with a state legislator.

There are many different approaches to advocacy. There are the traditional and still commonly used advocacy methods such as writing letters, making phone calls, and having face- to-face meetings. For people more focused on systems advocacy, many still provide public testimony or hold demonstrations or protests, often with media involvement. Over the past two decades, since the Action Letter Portfolio was first produced, technology has greatly advanced the tools advocates can use. Email now allows advocates to send their messages faster, easier and more broadly. Social media such as Facebook, Twitter, and online petition websites allow advocates to potentially reach and involve a greater number of participants in a more rapid fashion. The prevalence of use of smart technologies such as smartphones allows people to capture, present and share issues or problems with digital evidence (e.g., pictures and videos) in a more straightforward and timely manner.

No matter what advocacy methods or modalities you want to use, research shows that there are some basic and common elements to make you a more effective disability rights advocate. First, you need to know your needs and rights as a person with a disability under different laws. Understanding and knowing how to exercise your rights can help protect your interests and guide you to be a stronger advocate. In many situations, explaining how a law applies to a situation can bring about cooperation more quickly than when a person is relying on people to make change out of common courtesy. For example, laws such as the ADA specifically require reasonable accommodation and give examples in the regulations and technical assistance materials. Knowing the laws and your rights makes it easier for individuals with various disabilities to advocate in different situations.

Chapter 9 of this manual provides an outline of the major components of the ADA and many other disability laws. You may browse through Chapter 9 first to familiarize yourself with these laws or refer back to Chapter 9 anytime during the reading. ADA regulations, Standards, technical assistance materials, and enforcement guidance are available online at ADA.gov. You can also call the ADA Information Line (800-514-0301 (voice) and 800-514-0383 (TTY)) to ask questions and request materials.

Do not be intimidated by the legal language. After reviewing the regulations and technical assistance, the law will be easier to understand. You can always seek assistance from advocates who may be more familiar with disability rights laws. You might find them by contacting disability related organizations such as the Center for Independent Living in your community.

Second, you need to know how to communicate. Knowing your needs and rights is important, and then you need to be able to tell others what those are. Specifically, it is important for you to develop communication skills that enable you to be assertive as you negotiate, persuade, listen, articulate, and compromise.

Finally, yet importantly, be part of an advocacy effort. You may start by advocating for your personal concern. Then you can also join a group or start a group to work on a disability concern if you want to advocate for others or for a cause that has the potential to affect a local, statewide or nationwide change. You may well find that group advocacy is more effective than advocating on your own.

You can find a CIL in your community by checking the ILRU Directory of Centers for Independent Living

In our discussions with experienced disability rights advocates, they also recommended some strategies that can help you become a more effective advocate:

- Do your homework on the disability concern for which you want to advocate. It is important to know the concern well so you can be ready to talk about it and answer questions.

- Be accurate about the disability concern. Get the facts right and do not exaggerate. This helps you build your credibility.

- Be assertive, not aggressive. No matter how you communicate your disability concern (e.g., writing a letter, making a phone call), remind yourself to be positive about the change you seek. It is easy to get frustrated and angry when you advocate, but do not let anger get in the way when you communicate.

- Use empathy. It is important for advocates to get the reader, listener, or viewer to empathize with our point of view. This kind of understanding can lead to acknowledgement that our advocacy issue may have legitimacy.

- Use personal stories. Personal stories are great for advocacy. By telling compelling personal stories, we can let people know that what we advocate for has a real impact on actual human beings. Personal stories combined with data can make your advocacy more effective.

- Communicate to the right person(s). It is important to identify the person who has the authority to make changes to your disability concern. We can waste a lot of time and effort when we communicate with people who cannot make the decisions.

- Ask for help. When you feel that you are having a difficult time making sense of something or moving forward with your advocacy, ask for help! Many disability rights advocates (e.g., Center for Independent Living staff) are out there and can be your resources.

What can you learn from this manual?

This Advocacy Training Package is based on the Action Letter Portfolio (ALP), a training manual developed in 1998. The ALP was created to help people with disabilities learn how to conduct task analyses of disability concerns and write effective advocacy letters to address those concerns. This current manual updates that content and adds several chapters and information areas to include current methods of advocacy, such as the use of email, social media and digital evidence. Below is an overview of this training manual.

- Chapter 1 provides information on how to conduct task analysis of a disability concern or problem. Knowing how to analyze a disability concern is the first step to better understanding your concern and starting advocacy communication actions (e.g., writing an email or letter, making a phone call, using any pictures or video taken for documentation).

- Chapter 2 provides information on how to write an advocacy letter by introducing the components of an effective advocacy letter and demonstrating how to write an advocacy letter responding to a disability concern scenario.

- Chapter 3 provides information and practice opportunities to write one advocacy letter responding to an exemplar scenario and another one responding to one of your own disability concerns. We provide an advocacy letter template to assist you in writing letters.

- Chapter 4 provides exemplar letters for you to review and apply.

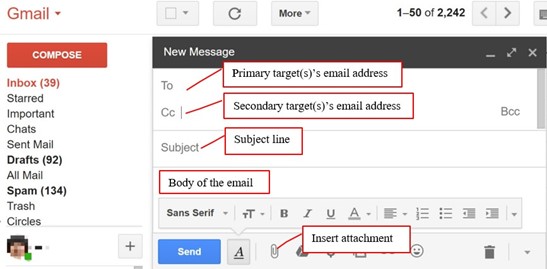

- Chapter 5 provides information on how to write an advocacy email. You will learn how to send an advocacy email both with and without an attached advocacy letter.

- Chapter 6 provides information on how to make an advocacy phone call. You will learn how to convey your message effectively during your phone call.

- Chapter 7 provides information on advocacy through social media. You will learn about what social media is and how you can use it to advocate for your cause.

- Chapter 8 provides strategies on how you can follow up with your initial advocacy communication.

- Chapter 9 provides information on the basic content of disability laws such as the ADA and Fair Housing Act.

- Chapter 10 provides a list of disability-rights related organizations and their contact information. Individuals with disabilities may obtain assistance such as information and legal assistance for advocacy from these organizations.

Chapter 1: Task Analysis of a Disability-Related Advocacy Concern

By Richard Thomson and Rajasekhar Allada, revised by E Zhang

Task Analysis of a Disability Concern

To advocate for a disability concern, you need to fully understand what the concern is and be able to convey that to the people who can make needed changes. Before you take any other actions, you should conduct a task analysis of the disability concern by asking and answering sevenquestions:

A task analysis is the first step to taking advocacy actions. You can use it to see what the real problem is and to determine if there are ways to solve the problem at a personal or group- benefit level. In many cases, this analysis will help break the concern down into a clearly stated issue that you can challenge and influence a positive change. The task analysis can help prepare you to start the communication process (e.g., a phone call, an in-person meeting, a letter, an email) to bring about changes. Specifically, the task analysis will outline what to communicate to whom.

A task analysis example

- What was the key disability concern? This is important in determining exactly what disability concern you will address. Is it lack of physical accessibility or employment discrimination or another issue?

- How did/does the concern directly affect me? This is important in determining the focus of the advocacy. An advocacy action becomes more credible when the disability concern has a direct effect on the individual who is the advocate. However, this is not to say that group advocacy is not effective, or that only those who personally experience a disability concern can take action to address it.

- Does this concern occur regularly or did unusual circumstances cause it to happen this time? This question may not always be relevant. When it is, however, it will help you to decide whether this is something that happened “just this once and may not possibly happen again,” or whether it is an ongoing issue that requires advocating for change.

- Who or what is the cause of the concern, and who can help make the changes? The answer to this question will help you to determine to whom the advocacy should be directed. Think about the primary and secondary agents of change who can help solve the concern. Find out their names and contact information.

- Is there a law or regulation that I can use to support a desired change? The answer to this question will help you develop solid reasons for your requested change. One reason people cannot ignore is that “the law requires” the change. If you are asking for something more than what the law requires, be honest about this and make a strong case for what is needed and why.

- Is there evidence or other information that can support my advocacy? The answer to this question will help you develop solid reasons as to why this is a problem and/or support your claim that there is a violation of law. If yes, then you need to collect the evidence or information before you start communicating your request. For example, you might take some pictures or measurements of physical barriers. Pictures can be very powerful evidence to help make your argument more convincing. Be sure to take multiple angles/views when taking photos.

- What changes do you want to see with the disability concern? The answer to this question will help you define the goal or end result of your advocacy. Do you want to see physical barriers removed or reasonable work accommodation provided? Be specific about the requested changes.

On March 5, Mark went to the newly built West Side Diner for supper. He had a hard time getting into the restaurant, as there was no curb ramp leading from the parking lot to the sidewalk. After getting in, Mark needed to use the bathroom. The bathroom interior stall door was too narrow for Mark's wheelchair to enter. The restaurant staff stated that there was no other bathroom available. Mark decided to wait to use the bathroom until he reached home, so he returned to his table where he endured slow service and poor food. After paying the bill that included an automatic 18% gratuity, Mark was angry and asked to speak with the manager. He explained to the manager that it was bad enough that the service was poor, but he found it intolerable that the new restaurant's restrooms were inaccessible for wheelchair users. The manager stated that Mark was treated no differently than the restaurant's other customers, and no one else had ever complained. Mark found out from the manager that the owner's name was James Smith.

The preceding scenario is an example of an occurrence that people with disabilities can encounter in their day-to-day lives. Title III of the Americans with Disabilities Act requires that newly built public accommodations be accessible according to the 2010 ADA Standards for Accessible Design. The ADA also requires that public accommodations that existed before January 26, 1993 must remove structural barriers when it is readily achievable to do so, which means easy to accomplish without much difficulty or expense. This will of course vary with the resource available to each business. Mark has many options open to him, but first he must clearly identify the problem and bring it to the attention of the proper authorities. The quickest way to resolve the problem may be to convince the restaurant owner to recognize the problem and voluntarily make the appropriate changes based on the ADA Standards. Mark must contact the owner to do this.

Task Analysis of Mark's Disability Concern

Mark conducted a task analysis of his disability concern by asking himself these seven questions:

- What was the key disability concern? The disability concern Mark faced that evening was the lack of accessibility to the restaurant entrance and to the men’s restroom stall. The slow service and required tip were not disability related.

- How did the problem directly affect Mark? First, Mark had a difficult time getting over the curb to go into the restaurant. Secondly, Mark could not use the interior restroom stall due to the narrow width of the stall door. Both barriers caused Mark great inconvenience and frustration. He could have faced social embarrassment and humiliation in a situation where he could not have waited to use the restroom.

- Does this appear to be a regularly occurring problem or did unusual circumstances cause it to happen this time? Both of these issues are a permanent problem in the built environment, and will be present each time Mark visits the restaurant, until the building's restroom and the outside curbing become accessible.

- Who or what is the cause of the concern and who can help make the changes? The restaurant owner James Smith would be the primary cause and agent of change of Mark's problem. Other potential agents of change include the architects who designed the building, and the city building inspector who signed off on approval of the building. The environment in and surrounding the restaurant was not wheelchair accessible, which was the central problem.

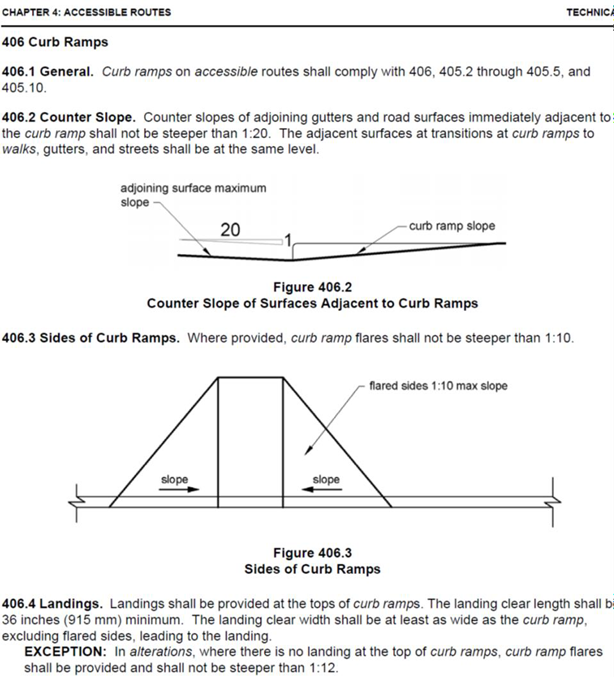

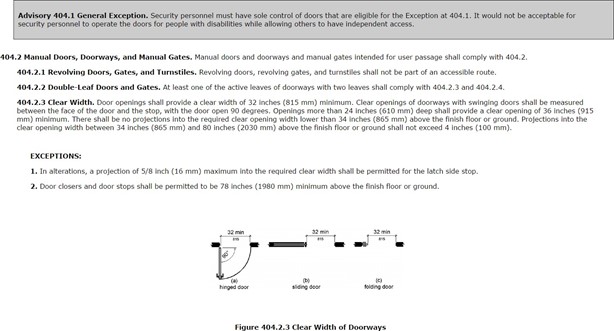

- Is there a law or regulation that Mark can use to effect a desired change? Yes, Section III of the ADA requires that all newly constructed public accommodations must be accessible and the 2010 ADA Standards for Accessible Design have standards that the restaurant needs to follow.

- Is there evidence or other information that can support Mark’s advocacy? Mark can go back to the restaurant, take a picture of the curb, and measure the width of the interior bathroom stall door to see if it complies with the 2010 ADA Standards for Accessible Design. (Even for older buildings, the 2010 ADA Standards requires that owners remove architectural barriers when it is readily achievable.)

- What changes does Mark want to see with the disability concern? First, the owner should have a curb ramp (also known as a curb cut) with a 1:12 slope ratio installed for wheelchair users to gain easy access to the sidewalk from street level. Second, the restaurant needs to install a wheelchair-accessible interior bathroom stall door with a minimum clear width of 32 inches, so all patrons can use the facilities when needed.

Now that Mark has answered these questions, he should have a better understanding of his disability concern and the changes and outcomes he wants to occur. After Mark completed the task analysis, his next step was to share the task analysis results to the right people. He considered the different ways to advocate, including letters or emails, phone calls, face-to-face meetings, etc.

In the following chapters, we will share how Mark can communicate to the restaurant owner through writing a letter, writing an email, or making a phone call.

Chapter 2: How to Write an Advocacy Letter

By Glen W. White, Richard Thomson, Rajasekhar Allada, revised by E Zhang

Now that you have learned how to conduct a task analysis for your disability concern, it is time to start the advocacy process. You have many choices of communication, such as writing a letter, making a phone call, or scheduling an in-person meeting. In some cases, you might use multiple approaches to advocate for your disability concern. This chapter will specifically focus on how to write an effective advocacy letter.

With the prevalence of electronic communications today, letter writing is still important, especially for sending a serious message about your disability concern. First, writing a letter allows you to present your thoughts and concerns with clear and convincing arguments. You can create a document for reflecting on your statement and further edit it before sending. Second, your letters will serve as an important “paper trail” as you undertake advocacy efforts to resolve your concern. They can even serve as evidence if your advocacy efforts eventually lead to legal actions. By keeping copies of all letters you send to your identified agents of change, you can show a trend of continued non-compliance if that occurs. This will make your advocacy case much stronger and provide additional support if at some point a formal complaint needs to be filed.

General Strategies for Writing an Advocacy Letter

In addition to the strategies in the Introduction, here are some general strategies about writing an advocacy letter:

- Write businesslike letters:

- Use a common 12-point font such as Times New Roman or Arial.

- Make your margins 1” all around the paper

- Make it single-spaced, with double spaces between different paragraphs.

- Type or print letters.

- Use quality paper that is white, if available. Avoid paper with cute decorations.

- Keep the letter short. One page, if possible. No more than 1.5 pages if you can.

- Be courteous. Even if you are writing about a concern, you can be courteous and should not sound “preachy.”

- Try to mention something positive about your experience (if any), while advocating for changing something negative with your intended agent of change/reader. For example, you can write, “I really enjoyed the food at your restaurant; however, the music was too loud for me to have a conversation with my friend as I wear hearing aids.”

- Emphasize the benefits of the changes, not only to you or other people with disabilities, but also to the intended reader. For example, making a business accessible will not only provide a better shopping experience for people with disabilities, but also potentially bring in more consumers with disabilities and their family members to build the business.

Components of an Advocacy Letter

An advocacy letter is one that clearly outlines a specific concern and a request for an action to address the concern. As an author, you should carefully organize your letter so it is easy to read and understand. The following list briefly describes each recommended letter component:

- Date your letter. You should address your concern on a timely basis – that is, as soon as you have identified or experienced the disability concern. The date at the top of your letter will show the parties involved that you are documenting when you formally addressed your disability concern. It also starts the clock ticking as to the time in which you expect a response.

- Inside address. Place the full name of the intended reader of the letter along with his or her title and the address at the beginning of the letter. You should always use the name and the title of the individual to whom you are writing, if possible, to show your respect.

- Salutation. This is the greeting of the letter. It should be directed appropriately towards the individual addressed in the “inside address.” For example, if you were mailing the letter to John Doe, City Manager, Anywhere, USA, you would open the letter with “Dear Mr. Doe.”

- Introducing yourself. Use the first two or three lines of the letter to tell briefly who you are and why you are writing.

- Introducing the problem and presenting the evidence. Explain the nature of the problem in detail: what occurred, when it occurred, how it affected you and other parties involved, and any actions you may have already taken. Present or mention any evidence of the concern that you have collected.

- Body of the letter. Provide the rationale for why there is a problem and what needs to be done to address the problem:

- 1. Explain how this concern has affected you personally, and how this concern can affect others and the intended reader (agent of change).

- 2. Cite any laws that apply to the situation you are presenting (See Chapter 9: Facts and Figures for more information).

- 3. Suggest reasonable solutions for how to address the disability concern if appropriate.

- 4. Offer yourself as a potential resource to contact if appropriate.

- Closing the letter

- 1. Wrap up the letter cordially with a brief review of the problem and your expectation about how the change agent will address your concerns. Emphasize the benefits of addressing the concern for multiple parties – you, the wider community, and the intended reader if possible. This will help finish the letter on a positive note.

- 2. Choose a closing such as “Sincerely” or “Sincerely Yours” to express to the intended reader your strong interest concerning this disability concern.

- 3. Add your signature. Leave four lines empty for your signature after the closing. You can sign the letter after you print it, or you can scan an image of your signature and affix it to this part of the letter. Black or blue ink is preferred.

- 4. Include your typed name and contact information. Type your name, title, address, phone number, email address, and any other contact information you want to include beneath your signature.

- 5. Make notes of enclosures. Note if you are enclosing additional documents for the reader to review. For example, “Enclosure: picture of the curb at the entrance.”

- 6. Note that you are sending copies of the letter to other important and relevant people. Send a copy of your letter to secondary agents of change who will be interested in or able to help resolve your disability concern. You can type “cc:” below the “Enclosure” line or your contact information if there is no “Enclosure.” “cc” stands for “courtesy copy.” For example, cc: Bob White, City Building Inspector;Paula Martin, City Councilwoman, 2nd District

- Mailing the letter. Before mailing the letter make sure that you:

- 1. Proofread the letter (e.g., check for spelling and grammatical errors and neatness).

- 2. Consider showing your letter to a friend for his or her feedback.

- 3. Check for correct address and adequate postage.

- 4. Make a copy to keep for your records (the copy may be very important for later advocacy actions).

Writing an Advocacy Letter: Mark's Example

Now that we know the components of an advocacy letter, let's take Mark’s problem and address each component of the letter as he chose to do.

Date your letter. Mark's letter should be dated sometime after March 5, the date his incident occurred. Mark will date his letter March 7, 2016.

Write the inside address. Mark will address his letter to the owner of the restaurant at the business address:

Mr. James Smith, Owner of Westside Diner

1600 Gerard Street

Anywhere, USA 66066

Salutation: Mark identified the owner's name so his salutation will read, Dear Mr. Smith:

Introducing yourself. Mark will introduce himself and give pertinent information as to why he is writing:

My name is Mark Post, and I am a wheelchair user. I am writing this letter to discuss some accessibility problems I encountered while dining at your restaurant.

Introducing the problem and presenting the evidence. Mark should relate the time of the problem and what occurred. Mark should also present or mention any evidence (e.g., measurement, pictures, and records) of the concern that he has collected. The previous introduction of himself should lead naturally into the problem:

On March 5, I went to your restaurant on Gerard Street and had a difficult time getting from the parking lot onto the sidewalk in front of your restaurant because there is no curb ramp to allow persons using wheelchairs to access the sidewalk from the parking lot. I’ve enclosed the picture of the curb entrance for you to review. Later I found myself unable to use the interior restroom stall door because it is too narrow (27 inches) for me to get in. At the time of the incident, I discussed my concern with Ms. Pam Barker, the shift manager, who suggested that I contact you since you are the owner of this business.

Body of the letter. Mark will now give supportive evidence and rationales as to why this problem is personally important to him and ideas as to how it might be solved:

It can be frustrating for a wheelchair user, like myself, to have several difficulties in one place of business. There are many wheelchair users and others with assistive devices like scooters and walkers, who like to go out to eat in our community. The physical barriers I have identified may be causing your business to lose other potential customers with disabilities. Even more importantly, the lack of accessible restroom stalls and a curb ramp from the parking lot to the sidewalk is not only an inconvenience – it does not comply with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). The ADA includes a provision that all newly constructed public accommodations be accessible. The addition of a 1:12 ratio curb ramp, a clear door width of at least 32 inches in the restroom stall and other accessibility features that may be needed in the restroom will bring about compliance with the 2010 ADA Standards for Accessible Design. I am very interested and willing to provide you with more information regarding making your restaurant accessible, including tax incentives that may be applicable to help offset the costs.

Closing. Mark will wrap up the letter by reviewing the main points and stating his expectation that the owner will address his accessibility concerns. He will choose a closing, sign the letter, type his name, address and contact information under his name if not using letterhead. He will also indicate that he included some supporting documents as “enclosures.” Then he will make a note that he is going to send a copy of his letter to the city code inspector and to the executive director of the local independent living center:

In closing, I would like to stress that your restaurant is required to be accessible for everyone, including wheelchair users. These access changes will help increase access to your business by all potential customers. I look forward to seeing the changes in your restaurant so that my friends and I may enjoy frequent visits in the future.

Sincerely,

Mark Post

1300 Brown St.

Anywhere, USA 55501

Phone: xxx-xxx-xxxx; Email:markpost@xxx.com

Enclosures: Pages of 2010 ADA Standards for Accessible Design regarding curb ramps and restrooms and a picture of the curb at the entrance.

cc: Hal Jones, Chief Code Inspector, Anytown; Betty Smith, Executive Director, Tri-County Independent Living Center

Mailing the letter. Mark is now ready to proofread his letter, show it to a friend, make any needed changes, sign it and keep a copy, check for correct address, affix postage, and mail the letter to the appropriate people. Please see the next page for Mark's finished letter.

Mark's Letter

March 7, 2016

Mr. James Smith, Owner of Westside Diner

1600 Gerard Street

Anywhere, USA 66066

Dear Mr. Smith:

My name is Mark Post, and I am a wheelchair user. I am writing this letter to discuss some accessibility problems I encountered while dining at your restaurant.

On March 5, I went to your restaurant on Gerard Street and had a difficult time getting from the parking lot onto the sidewalk in front of your restaurant because there is no curb ramp to allow persons using wheelchairs to access the sidewalk from the parking lot. I’ve enclosed the picture of the curb entrance for you to review. Later I found myself unable to use interior restroom stall door because it is too narrow (27 inches) for me to get in. At the time of the incident, I discussed my concern with Ms. Pam Barker, the shift manager, who suggested that I contact you since you are the owner of this business.

It can be frustrating for a wheelchair user, like myself, to have several difficulties in one place of business. There are many wheelchair users and others with assistive devices like scooters and walkers, who like to go out to eat in our community. The physical barriers I have identified may be causing your business to lose other potential customers with disabilities. Even more importantly, the lack of accessible restroom stalls and a curb ramp from the parking lot to the sidewalk is not only an inconvenience; it does not comply with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). The ADA includes a provision that all newly constructed public accommodations be accessible. The addition of a 1:12 ratio curb ramp, a clear door width of at least 32 inches in the restroom stall and other accessibility features that may be needed in the restroom will bring about compliance with the 2010 ADA Standards for Accessible Design. I am very interested and willing to provide you with more information regarding making your restaurant accessible, including tax incentives that may be applicable to help offset the costs.

In closing, I would like to stress that your restaurant is required to be accessible for everyone, including wheelchair users. These access changes will help increase access to your business by all potential customers. I look forward to seeing the changes in your restaurant so that my friends and I may enjoy frequent visits in the future.

Sincerely,

Mark Post

1300 Brown St.

Anywhere, USA 55501

Phone: xxx-xxx-xxxx; Email:markpost@xxx.com

Enclosures: Pages of 2010 ADA Standards for Accessible Design regarding curb ramps and a picture of the curb at the entrance.

cc: Hal Jones, Chief Code Inspector, Anytown; Betty Smith, Executive Director, Tri-County Independent Living Center

[Enclosure: Pages of 2010 ADA Standards for Accessible Design]

Enclosure: Photo of curb without ramp or cut.

Chapter 3: Practice Writing an Advocacy Letter

By Richard Thomson, Rajasekhar Allada and Glen White, revised by E Zhang

1. Practice Writing an Advocacy Letter

Now that you have learned the steps involved in writing an advocacy letter, you can practice writing one on your own by responding to the following scenario. When writing your practice letter, make up the date and addresses for Barb and the individuals to whom you are sending the letter.

Barb Davis is a 23-year-old recent college graduate with epilepsy. She controls her seizures with medication and leads an active life. On February 22, she applied for and obtained a job as an Inventory Control Specialist for The Morgan Company, a small appliance manufacturing plant with 30 employees that does subcontracting work for White & Decker. Her job involves maintaining an accurate count of the inventory of materials used by the plant workers to assemble small appliance products. Barb's job performance in her position has been satisfactory and she will receive her three-month probation review on May 20.

Barb is called in for a meeting with Mr. Hector Lopez from the Human Resources Department on April 20. Barb is excited because she thinks that the meeting's purpose is to take her off probation early because of the excellent job she has been doing. However, Mr. Lopez delivers the bad news---the plant is discharging her. Apparently after talking with Mr. Ira Miser, the plant's Director of Operations, there is excessive concern that Barb will have one of her “fits” and hurt herself by falling to the floor. Repeated incidents of these "fits" may drive up the costs of the plant's group insurance plan. Barb goes home devastated after cleaning out her desk at work. Barb felt that she was discriminated against by the company because of her disability. She decided to advocate for herself by writing a letter.

Now that you have the information, place yourself in Barb’s shoes and write up a task analysis of Barb’s disability concern. Please do your own work here; at the end of this chapter we will present a task analysis and advocacy letter for your comparison.

1.1 Task Analysis

TIP: When writing your task analysis, be as descriptive as you can; come to the point, but give sufficient information to add context.

1) What is Barb's main disability concern?

2) How does the problem directly affect Barb? (In her job? For her immediate future?)

3) Does this problem occur regularly or did unusual circumstances cause it to happen this time?

4) Who or what is the cause of the problem and who can help make the changes?

5) Is there an existing law that can be cited to advocate for a desired change?

6) Is there evidence or other information that can support Barb’s advocacy?

7) What specific changes does Barb want to see happen with the identified disability concern?

1.2 Writing the letter

Instruction: Please write a letter for Barb using the template below. You can click on the instructional text to enter your content. The entered content will replace the instructional text. The content in the brackets [ ] can be deleted if it does not apply to you. Otherwise, you can replace it with information that is pertinent to you (e.g., your phone number).

Date

Name, Title Company Street address

City, State zip code

Salutation such as Dear Mr. XX:

Introduce yourself by telling who you are and why you are writing, using two to three lines.

Introduce the problem and present the evidence: explain the nature of the problem in detail, what occurred, when it occurred, how it affected you, all parties involved, and any actions you may have already taken. Present any evidence of the problem that you have collected.

Body of the letter: Provide a rationale as to why the reader should work to resolve the problem. Explain how this concern has affected you personally, and how it can affect others and the target reader. Cite any laws that apply to the concern. Suggest possible solutions to the concern. Offer yourself as a potential resource to contact if appropriate.

Closing: Wrap up the letter cordially with a brief review of the problem and your expectation that the primary intended reader will take prompt action to address your concerns. Emphasize the benefits of addressing the concern for multiple parities, including the reader if possible.

Closing with expressions such as “Sincerely,” or “Thank you.” [Sign here]

Name, Title Street address

City, State zip code

[Email: example@example.com] [Phone: (000)-000-0000]

[Enclosures]

cc: name and title of people who you identified as secondary contacts

1.3 Example response of Barb

Let’s review Barb’s task analysis and advocacy letter responding to her dismissal from The Morgan Company.

1.3.1 Task analysis

1) What was Barb's main disability concern?

Barb's main disability concern is that she was fired for having epilepsy due to fears about her condition, even though she has performed the job satisfactorily. Barb lost her job based on her disability and not on her performance. Her disability did not pose an immediate risk to herself or others.

2) How did the problem directly affect Barb?

If termination from this job cannot be reversed, Barb would likely suffer a financial loss, personal humiliation, and possible difficulties obtaining future employment if this company provides a negative reference to other prospective employers.

3) Does this appear to be a regularly occurring problem or did unusual circumstances cause it to happen this time?

It would be a regularly occurring problem if the company has discriminated against other employees with disabilities. However, there is not enough information about the experience of other employees with disabilities of this employer to determine whether this is a one-time or regularly occurring problem

4) Who or what is the cause of the concern and who can help make the changes?

The cause of the problem in Barb’s case is the plant manager, Ira Miser. Although Mr. Lopez was the person who gave her news of the dismissal, it was Mr.

Miser’s decision to have her terminated. In this case, Barb would want to write to Mr. Miser as a primary agent of change about her unjustified termination. When identifying your primary contact with employment-related advocacy concerns, be sure to check out whether there is an established written grievance procedure in your company and use it accordingly.

In addition, Barb thinks that it can be helpful to write to the Morgan Company’s HR department since they are likely involved in all hiring and firing decisions, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, her State Disability Rights Office, her legislative representative, and the National Epilepsy Foundation.

5) Is there an existing law that can be cited to advocate for a desired change?

The company has violated Title I of the Americans with Disabilities Act, which prohibits discrimination in all hiring practices, including job application procedures, hiring, firing, advancement, compensation, training, and other terms, conditions, and privileges of employment. In addition, an employer may not simply assume that a threat exists; the employer must establish through objective, medically supportable methods that there is significant risk that substantial harm could occur in the workplace. Barb was terminated because of her disability, not because of her job performance. It is quite clear that the company has no evidence that Barb poses a direct threat to herself or others. There were no documented examples of Barb having seizures at work; most of the concerns about her seizures were based on hearsay.

6) Is there evidence or other information that can support Barb’s advocacy?

First, Barb can show evidence of her attendance and punctuality at work and a report on the accuracy of the inventory control that she maintains. She can also present recent medical records and a letter from her physician stating that her seizures continue to be well under control.

7) What specific changes does Barb want to see happen with the identified disability concern?

Barb wants the company to correct their decision of firing her based on her disability and to give her job back to her.

Now that we have identified Barb’s specific disability concern, let’s start to write the actual action letter.

1.3.2 Writing the letter

April 21, 2017

Mr. Ira Miser, Director of Operations

The Morgan Company 1212 Main St.

Anywhere, USA 66100

Dear Mr. Ira Miser:

My name is Barb Davis and I have worked at your plant for the last two months as an Inventory Control Specialist. I have a college degree relevant to the area of inventory control and have been doing excellent work. I also happen to have epilepsy, which is controlled by medication and which is not relevant to the area of inventory control or to my current job. I am writing to discuss with you the fact that I was fired because of my disability.

On April 20, I was called into Mr. Lopez's office in the Personnel Department and informed that I was to be terminated. I was extremely upset to learn that you had based the decision to terminate me on my epilepsy and not my performance. Mr. Lopez explained to me that you were concerned I would have “fits” which could drive up the rates of the Morgan Company’s employee health insurance. I understand your concern for my personal safety and for the financial management of the company; however, as stated above, my epilepsy is controlled by medication. My enclosed medical records from last year can prove this.

I don't believe you will ever really comprehend how I felt when I was told that I was to be terminated. I actually believed that I was being called into Mr. Lopez's office to be told that my probation period was ending early due to the quality of work I had demonstrated. I truly feel that if you discuss with Mr. Lopez the quality of my performance, you would realize that you have just let go a valuable employee and would immediately wish to address my concerns. My epilepsy has not interfered with my job performance at any point in my academic or professional career. For you to base your decision on my epilepsy is not only wrong and unfounded, it is also illegal.

The Americans with Disability Act (ADA) specifically states in Title I that all hiring and “firing” practices are prohibited based on discrimination due to disabilities. What you have done is discriminate against me based on my disability, which is a violation of the ADA. I am in the process of retaining a lawyer and starting the necessary proceedings to get my job back.

However, I am writing this letter hoping that you will review your decision and rehire me because I am a valuable employee who has performed my job beyond company expectations. With regard to the insurance premiums, I think that you will find that the type of seizures I have will not place me, other employees, or the facility in any immediate risk of harm.

In closing, I hope that you understand that this letter is an attempt to avoid an unnecessary legal action. I enjoyed the work that I performed for your company, and would be happy to return to work. Reviewing this decision will not only be important to my career, but also help your company comply with the ADA. I hope that you will reconsider your decision and that we can settle this amiably without having to take legal action.

Sincerely,

{Sign here]

Barb Davis

1515 Downtown St.

Anywhere, USA 67612

barbdavis@gmail.com

Phone: (000)-000-0000

Enclosures: Medical records from 2016-2017

cc: Adrienne Tuttle, Region VII EEOC Information Officer Anystate Disability Rights Office; John F Smith, US Representative, 8th District; The Epilepsy Foundation

2. Writing your personal concern advocacy letter

After reviewing the presented disability scenarios, you have learned the basics on how to write an effective advocacy letter. Now it is time to start writing an advocacy letter about your own disability concern. Again, it is important that you recognize your personal needs and strengths, and your rights based on applicable disability rights laws. As a person who has personal experience with a disability, you are uniquely suited to identify relevant issues that affect you and/or other people with disabilities. Also, whether you are writing a letter or an email, remember to be courteous. Even if you are upset or angry about your concern, strive for a positive and constructive tone of voice. People are more likely to work with when you approach them with respect.

In this section, we will describe how you can personalize your advocacy letter to increase the likelihood of achieving your objectives.

2.1 Identifying your personal disability concern

When preparing to write an advocacy letter, it is important to define the issue you wish to address clearly. This is not as easy as it might seem. Some issues are very large and complex, such as employment discrimination against people with disabilities. Where does one start with such a general and overwhelming issue?

At the other end of the spectrum, some issues such as the lack of accessible faucets on a bathroom sink may seem rather insignificant. Yet, in each case, such issues will undoubtedly be of concern to some people with disabilities. This section will identify criteria you can use to identify a personal disability concern.

2.1.1 Identify an issue which is either very serious or irritating, and which occurs on a frequent basis.

For example, a serious issue might be the inaccessibility of a newly constructed government building, while a frequently irritating issue might be the lack of enforcement of accessible parking regulations. Not all issues are negative in nature. Some advocacy efforts can be in support of a positive disability initiative that may be at risk of losing funding. Whether a serious issue or a smaller annoying one, you must decide if this is an issue you wish to tackle by yourself or with others.

2.1.2 Determine whether this is a personal or systems advocacy cause.

Some disability concerns may be personal and only affect a specific person in a specific situation. For example, a person with a disability applies for a job and is discriminated against when the job is given to a less qualified non-disabled person. In this case, the individual would advocate using the ADA to address a personal concern. In another example, a wheelchair user cannot “weigh-in” each week as other members do after joining Weight Watchers because there is no accessible scale. Since this could affect many other members with disabilities, systems advocacy, where people unite, might be a more effective way to affect change.

In some other situations, addressing a personal disability concern might benefit many others as well. An example of this might be a wheelchair user who uses paratransit. The transportation system currently runs from 8 am to 5 pm, but the passenger wants to go out for evening or weekend excursions as well. The wheelchair user in this case could advocate for a change of schedule, but might have more success if she also asks others who use the paratransit system to join this advocacy effort. The critical weight/mass of multiple riders will be more compelling to the administrators of the paratransit system. This is how the advocacy group ADAPT helped get the American Public Transit Association to finally start ordering fixed route buses with kneeling lifts. Is your disability concern personal or systemic?

2.1.3 Clarify your concern(s) and break it down into a winnable situation.

Some disability concerns may be large and complex. Some may require a lengthy period to resolve. One other strategy can be to break the particular disability concern down into what Steve Fawcett (1991), in "Some values guiding community research and action." called “Small Wins,” that is, smaller goals or units of change that are more likely to lead to success. To do this, analyze your concern and determine which units are most important. Ask yourself,

- Have I identified a specific disability concern in which action could be taken?

- Have I identified specific actions that can be taken to address this issue?"

- Is this something about which the person or organization I am writing to can do something?

If the answer to these questions is YES, chances are you have a potential winnable action issue.

2.2 Inserting convincing and accurate information in your letter.

Once you have identified the disability concern, it is time to write the letter. Strategies for writing advocacy letters discussed in previous chapters will not be addressed in detail here.

It is important that you provide reasons as to why you are addressing the issue to the identified person or organization. The letter should also include any relevant municipal, state, and federal laws that support your position. In some cases, the organization or person may be unaware that your disability concern is even a significant issue. On the other hand, the individual or organization may be reluctant to address a disability concern any more than necessary.

Identifying specific laws that they must comply with alerts them to a situation that could result in legal action. For your convenience, we have developed a section entitled “Facts and Figures” (see Chapter 9). This chapter provides specific information on laws and regulations that you can include in your letters to give them greater credibility and influence.

2.3 Selecting the most appropriate individuals for your action letter.

Identify the person who has the authority to make changes as your primary contact/reader. It is a good idea to go as high as you can go in the authority chain for change to happen. Additionally, it is a good strategy to send copies of your advocacy letters to other important and relevant people. This will increase the likelihood of a response from your primary contact. The next section will identify primary and secondary agents of change/contact to whom you should send your action letters.

1) Identify the person with whom you have the most advantage. Sometimes you can more readily address a problem when you send your letter to a person that you know (e.g., a colleague in the construction and design department for an elevator that tends to be broken a lot). Or, you may have a mutual friend with the primary contact to whom you can refer to in your letter.

2) Go to the top whenever you can. The upper level staff of an organization are more likely to have the authority to change things and, therefore, may be more flexible in interpreting and implementing policies. Staff at the lower levels of an organization often do not have the authority to make decisions about organizational policies. Your time and resources are precious. Use them where they will do the most good – start at the top! You have to be realistic when starting at the top. It’s probably not the best idea that you have the initial contact with the Chief Executive Officer of an airline because your wheelchair was broken. But there is likely someone down the corporate ladder who can help you.

3) Select for empathy. When selecting your primary contacts, try to find individuals who may have experience with a disability. This may be a personal disability, or contact with family, associates, or friends who have some type of disability. Such experiences may have already sensitized the person to the needs of people with disabilities.

4) Think systematically. Have you captured the big picture in identifying your primary contact? For example, if you are working with a local franchise (one business that is part of a larger chain), you might contact the local manager first to describe your disability concern. If you do not get any response at this level, you might then contact the regional manager, and send a copy of your advocacy letter to the corporate (highest level) office. Officials in these offices want all of their franchise businesses to provide consistent services and products, and to maintain a positive community image. Thus, your actions at this level may trickle down in the form of orders from the executive offices for a local franchise to make specific changes in compliance with the ADA, or other requested accommodations.

5) Research the information. The telephone and internet can become your tools when trying to find the names of the individuals you wish to reach. Do not be afraid to call the manager and ask for the name and business address of the owner. Or try searching the contact information online. It may take some investigative work to find the individual who will be most effective in helping you; however, the time that it takes to research the information will be worth it in the end.

When writing to your primary contact, consider copying your letter to other influential secondary contacts6. By doing this, you let the person or organization with whom you have a disability concern know that others are aware of your request. Cautionary note: If you are writing a letter to a primary contact that is of a personal nature and could potentially be interpreted as slanderous (i.e., injurious to the reputation of the person you are writing), you may wish to seek legal counsel as to whether or not you should send copies to other people. These secondary contacts are likely to be interested in the action or non-action that the primary contact takes. This simple act of sending copies of your letters to secondary contacts increases the accountability of the primary contact to make a timely and positive response to your request. Depending upon the severity of the disability concern, you may wish to copy the letter to two, three, or four different individuals or organizations.

When copying people, be sure to indicate their position and organization so that the primary contact will know who else is informed of the matter. See the example below:

cc: R. Gutierrez, Director, Hispanic Health Coalition for the Rio Grande Valley; J.C. Lopez, Project Director, Latino Health Enterprises

1) Government Entities. Potential secondary contacts for this category include, but are not limited to the following entities:

| Federal | State | County and Local |

|---|---|---|

| President | Governors | County Executive or Administrator |

| Senators | State Legislature | County Commission |

| House Members | Secretary of State | District Attorney |

| Congressional Staff Members | State Attorney General | Mayors or City Administrators |

| National Council on Disability | State Budget Director | Mayoral Disability Committee |

| Department of Justice | State Director of Vocational Rehabilitation | Human Rights Commissioners |

| Department of Transportation | Human Rights Commissioner | Building Inspectors |

| Department of Commerce | Department of Social Services | City and County ADA Coordinators |

| Office for Civil Rights | State ADA Coordinators | |

| Equal Employment Opportunity Commission | ||

| United States Access Board | ||

| Federal Aviation Administration |

2) Businesses. Potential secondary contacts for this category include, but are not limited to, Better Business Bureau, Chamber of Commerce, Corporate Headquarters, District Managers, Professional Trade Groups or Guilds of which the business may be a member.

3) Medical. Potential secondary contacts for this category include, but are not limited to, Council on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities (CARF), State Medical Examiners, American Medical Association, State Medical Associations, and specific Medical Specialty Organizations (e.g., American College of Surgeons).

4) Disability Advocacy Organizations. Potential secondary contacts for this category include, but are not limited to the following:

- Centers for Independent Living

- ADA National Network and Regional ADA Center

- State Developmental Disability Councils

- State Protection and Advocacy Organizations

- Client Assistance Programs

- Paralyzed Veterans of America (PVA)

- National Council on Independent Living

- Statewide Independent Living Councils

- Association of Programs for Rural Independent Living

- Americans Disabled for Attendant Programs Today

- The Arc

- National Disability Leadership Alliance

- American Civil Liberties Union

- Disability Rights Education Defense Fund

2.4 Sending your letter

Sending your letter to your intended contacts may seem easy enough; however, you should be aware of advantages and disadvantages of the different methods for sending your letter. We will discuss each briefly below.

2.4.1 First Class Mail.

This is the most common method of sending mail. If you are not in a hurry and the disability concern you are writing about is not critical, sending your letter by first class mail is a low-cost and effective choice.

2.4.2 Certified Mail.

This method virtually insures that the person to whom you are sending your letter will receive it. It provides proof of mailing, including time of mailing and the date and time of delivery or attempted delivery. Remember to request a return receipt to confirm delivery. You can choose this method if you want to ensure that your letter gets to its intended reader by a specific date.

2.4.3 Registered Mail.

Registered mail is very similar to certified mail, except that it also includes an option to purchase insurance in case the contents of the letter or package are destroyed or lost.

2. 4.4 Federal Express/UPS.

Federal Express (FedEx) or United Parcel Service (UPS) are other ways to get your letter and accompanying documents to the addressee in a timely manner. These services are more reasonably priced than they used to be.

2.4.5 Facsimile (FAX).

Most offices will usually have at least one FAX machine to serve its workers. Many printers or scanners now have fax capability. FAX machines are very flexible in that they allow graphics, tables, and text to be sent across the phone lines to the intended receiver. The transmission is immediate and the sender is notified if the FAX message did or did not get through to the receiver.

Cautionary Note: Sending a FAX is a less formal approach. This method does not guarantee confidentiality of your letter's content. Generally, letters of this nature are not sent via FAX, unless the receiver of the letter agrees to it. Also, note that sending a FAX to the primary contact does not guarantee that they will receive it.

2.4.6 Electronic Mail (Email).

Email is currently the most frequently used form of communication. It is fast and without any cost as long as you have access to the internet and a computer. Traditionally, mailing a letter shows a formal approach to communicating with others. It implies that you went through the time to type or write your letter, put it in an envelope, place postage on the envelope and mail it. However, with easy access to internet and other communication modes, some individuals opt for speed versus formality.

There are two different ways to send an email to advocate for your disability concern. You can either send an email with an attached advocacy letter or you can write your advocacy email directly in the text of the email. There is no evidence to determine which approach is more effective. However, one suggestion might be that if you want to send a more formal email, such as one with letterhead or signature, then you should send an email with the letter as an attachment. Some strategies for sending an advocacy email will be discussed in Chapter 5.

Now you will have a chance to write your own advocacy letter to address a specific disability concern you have. Remember that the first step in writing an advocacy letter is to perform the task analysis. If you need some assistance with this, turn back to Chapter 1.

2.5 Task analysis

1) What is your main disability concern?

2) How does the problem directly affect you?

3) Does this problem occur regularly or did unusual circumstances cause it to happen this time?

4) Who or what is the cause of the problem and who can help make the changes?

5) Is there an existing law that can be used to advocate for a desired change?

6) Is there evidence or other information that can support your advocacy?

7) What specific changes do you want to see with the disability concern?

2.6 Writing the letter

Instruction: Please write a letter for your own disability concern using the template below. You can click on the instructional text to enter your content. The entered content will replace the instructional text. The content in the brackets [ ] can be deleted if it does not apply to you.

Otherwise, you can replace it with content that is pertinent to you.

Date

Name, Title Company Street address

City, State zip code

Salutation such as Dear Mr. XX:

Introduce yourself by telling who you are and why you are writing, using two to three lines. Introduce the problem and present the evidence: explain the nature of the problem in detail, what occurred, when it occurred, how it affected you, all parties involved, and any actions you may have already taken. Present any evidence of the problem that you have collected.

Body of the letter: Provide a rationale as to why the targeted reader should work to resolve the problem. Explain how this concern has affected you personally, and how it can affect others and the target reader. Cite any laws that apply to the concern. Suggest possible solutions to the concern. Offer yourself as a potential resource to contact if appropriate.

Closing: Wrap up the letter cordially with a brief review of the problem and your expectation that the primary target reader will take prompt action to address your concerns. Emphasize the benefits of addressing the concern for multiple parities, including the target reader if possible.

Closing with expressions such as “Sincerely,” or “Thank you.” [Sign here]

Name, Title

Street address

City, State zip code

[Email: example@example.com] [Phone: (000)-000-0000] [Enclosures]

cc: name and title of people who you identified as secondary contacts

Chapter 4: Exemplary Letters

4.1 Accessible parking example

November 20, 2016

Mr. Robert Bruce, Manager Public Department Store

322 Main Street

Anytown, Anystate 33011

Dear Mr. Bruce:

I am a longtime customer and credit card holder at your store. I have always found excellent merchandise at a fair price at Public Department Store and, until recently, have always enjoyed good service. However, when I visited your store with my daughter yesterday, an extremely upsetting incident occurred. My 10-year-old daughter, Lori, uses a wheelchair and I drive a van with a side entry lift to accommodate her needs. Because your parking lot lacks accessible parking spaces, I had to park diagonally across two parking spaces to ensure that we will not be blocked in on the passenger side so that she can reenter the van when we finish shopping. Although I have spoken with store employees at the customer service desk several times in the past about the need for accessible parking in your lot, nothing has been done so I have felt justified in taking up two parking spaces to accommodate my daughter's needs.

Yesterday when we emerged from the store, we found a store security guard waiting at our van to inform us that he would call the police if it wasn't moved immediately. Apparently, he was angry because the parking lot was full and we were taking up two spaces. My daughter and I tried to explain our reasoning to him, but he became more loud and rude, and finally told us “my crippled daughter was not the store's problem.” Upon hearing this, we got into the van and left, as I did not want my daughter exposed to any more of this disgusting behavior.

I am writing to demand three things. First, a written apology from your store on behalf of this employee, who refused to give his name. Second, an assurance that you will provide your staff with disability awareness training to prevent incidents like this from happening again. Third, evidence of when Public Department Store plans to comply with the Americans with Disabilities Act by designating accessible parking spaces as required by law. If this modification is not prioritized and completed promptly, I will file a complaint with the U.S. Department of Justice and will work with advocates at Central Independent Living Center to publicize your employee’s lack of sensitivity and your store’s lack of adherence to the law.

I look forward to your prompt response regarding this very serious matter.

Yours truly,

Janet Best

3322 Flower St.

Anycity, Anystate 33011

Phone: 111-111-1111

cc: Joe Brown, Central Independent Living Center Susan Scott, Anytown ADA Coordinator

4.2 Disability policy example

Feb. 22, 2017

June Graham, Councilwoman

1029 Worthington Street

Westham, Anystate 10002

Dear Ms. Graham:

I am the parent of an adult with intellectual disability. My son will be affected by the proposed zoning changes involving rental properties in the city of Westham that you supported at last night’s city council meeting. I want to advise you of the difficulties that these changes will create for a significant number of citizens.

As I'm sure you are aware, there has been a movement to improve housing arrangements for persons with intellectual disabilities. This movement has fostered the development of homes and apartments integrated throughout the community, instead of the larger group homes and institutions which create segregation and stigma. For the last 18 months, my son, John, has shared an apartment near the downtown area with another man with whom he works.

These two men receive social support and supervision from a local agency, Community Supports. For the first time in his life, John has been free to do the things that he enjoys when he wants to do them, an opportunity he did not have when he lived in a group home with seven other adults.

Because of this housing change, John has improved his productivity at Pizza Hut, where he maintains the salad bar. He has been getting along better with his roommate, his support staff, his friends, and his family. He has also gotten to know some of his neighbors, who have been very friendly and helpful to him. In short, he has been a much happier and satisfied person since his living arrangements have allowed him the same privacy and choices that most other adults in society enjoy.

Unfortunately, due to the proposed zoning changes, rental of housing in John's neighborhood may be severely restricted. John may have to leave the apartment which is comfortable, affordable, and which is close enough to his job for him to walk to work. Because of the zoning change, John and others needing similar living arrangements are likely to have difficulty finding affordable, convenient housing. I fear that it may force many of these people to return to the group homes and institutional living arrangements that were so detrimental to their happiness and integration in the community.

Please reconsider your support for the zoning changes and consider those who need to rent apartments in these areas and who have worked so hard to become contributing citizens of this community. A policy that restricts safe, affordable housing for lifelong residents who have overcome many societal barriers cannot be a good one for the community. I look forward to receiving your response and to discussing this important issue with you.

Sincerely yours,

Marion Kaye

1110 Mason St.

Westham, Anystate 10002

cc: Larry Donnelly, Director, State Developmental Disability Council; Mary Black, Director, Anytown Arc

December 7, 2016

Representative Edward Main, District 30

585 South 19th Street

Anytown, Anystate 11111

Dear Representative Main:

My name is Joy Kent and I was born and raised in Anytown. I enjoy living in Anytown because people still smile and wave. I am 49 years old and I have severe major depression. Since age 10, I have had depression, but it has only been in the last 8 to 10 years that I was diagnosed with severe depression. I would really like to be working doing computer repair work, but my depression frequently gets in the way.

I use mental health and other health care services through Anystate Medicaid. Recent cuts to Medicaid services have limited my access to needed Psycho-Social Rehabilitation (PSR) services, and have eliminated my access to dental care. Without adequate PSR services, when my life goes into crisis the only support available is to send me to the behavioral health unit at the hospital. This has happened twice in the past year, and the cost to the state each time was about $48,000.

The last time I saw my dentist was three years ago. My teeth are cracking; I need new fillings. If my teeth don’t get some attention soon, I am afraid I must have implants or dentures, which costs so much more to the state than basic preventive care.

I am also very concerned about the change to Managed Care in Anystate Medicaid. I currently have a very good counselor and a very good PSR worker. Will I get to keep them as my service providers under managed care? Will there be an incentive for a Managed Care Organization to keep me out of the hospital and to do everything they can to keep me living in the community with the support I need to be healthy? These and other questions need to be answered for the new system to be effective.

I am asking that there be no more cuts to mental health services, that dental services be restored to adults with disabilities, and that we take our time with Managed Care to build a quality service delivery system for adults like me with mental health issues. I hope you can agree that there is a real problem in our state with the lack of mental health services, and that dental care is important to helping people remain healthy and productive. I ask that you be willing to work to resolve these issues this session, and I will do what I can as well. Peoples’ lives depend on it. I know mine does.

Please contact me if I can provide any further information that can assist you to perform this important work.

Sincerely,

Joy Kent

123 4th St

Anytown, Anystate 11111

Phone: 000-000-0000

4.3 Education example

October 16, 2016

Susan Sandford, Director of Special Education

Anytown County School District

5674 Brown Road

Anytown, Anystate 11001

Dear Ms. Sandford:

My son, Frederick Sutton, is a student at East Junior High School and has been classified as learning disabled for the past year. As his parent, I am very concerned that Frederick get a good education so that he can succeed in the future. My son enjoys school and especially enjoys being involved in the chorus and in sports.

As stated in his Individualized Education Plan, which was approved and adopted last May and which was to be implemented at the start of this school year, Frederick should have access to a computer each day during the time he spends in the resource room. He was to use this equipment to get help with his assignments in English Composition.

As of this date, he has not had access to a computer in the resource room and neither his teacher, Mrs. Abbott, nor the principal, Mr. Smith, can tell me when a computer will be available for his use. He is falling behind in his English Composition class, and I am afraid that it will become harder and harder for him to catch up with the other students in the class if he does not gain access to the computer specified in the IEP.

I am requesting that my son be given daily access to a computer in his resource room upon your receipt of this letter. I believe that his rights under his IEP are currently being violated by the school district, and I have been advised by an advocate from Schools Are For Everyone (SAFE), Meg Ferguson, that I should notify the Special Education Bureau of the State Department of Education if the problem is not resolved immediately.

I hope that you will work with me in this very important matter to ensure my son’s continued education.

Sincerely,

Paul Sutton

4411 Boone Ave.

Anycity, Anystate 11001

Email: pualsutton@example.com; phone: 111-111-1111

cc: Meg Ferguson, Schools Are For Everyone (SAFE); Brian Brown, Legal Services of Anytown County

4.4 Employment policy example

February 5, 2017

Mr. Todd Rice, Manager

Curley's Chicken Coop

1005 Grandview Avenue

Anytown, Anystate 44001

Dear Mr. Rice: